Global Mental Health in Asia Symposium Day 3 Panel 1

- October 23, 2025

- 1:00 pm

Summary

A multidisciplinary panel discussed the urgent need for more research and action at the intersection of climate change and mental health. Current gaps exist in data collection, especially among vulnerable and marginalized groups. Panelists emphasized community-driven interventions, the importance of integrating mental health into climate policy, and global collaboration. There is consensus on the need for rapid, actionable research to inform effective, equitable policy and funding priorities.

Raw Transcript

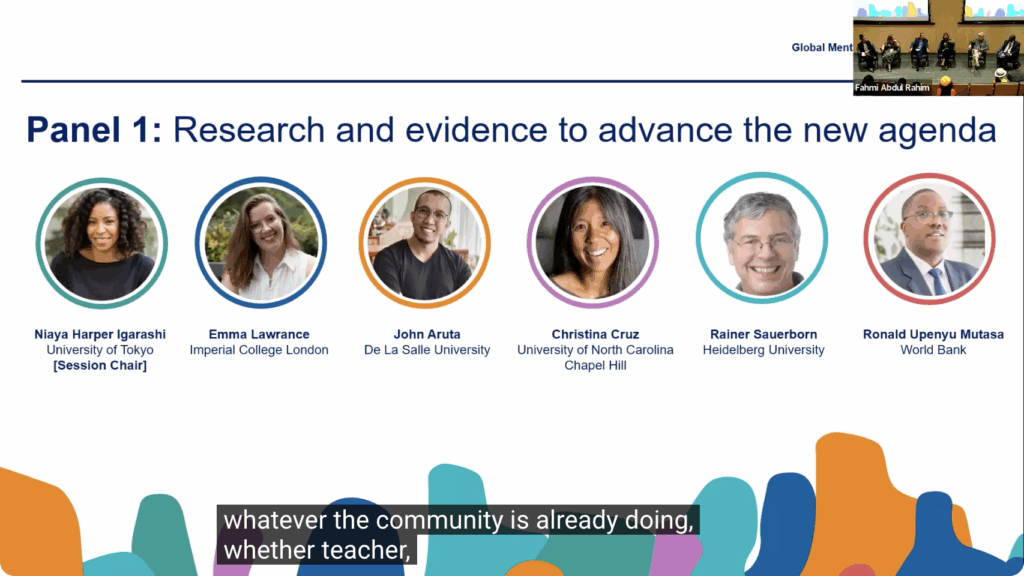

[00:00] And to introduce our panel and to moderate this session, I would like to invite our research fellow from the Health and Global Policy Institute in Japan. She is also a PhD student from the University of Tokyo, Naya Harper-Igarashi. Naya?

[00:20] The mic is yours. And can we invite the panelists to already take your seats? Yep, you can just follow your order in the post. In the post. Is it? Okay, yeah, thank you. So yes, thank you. So I'm Naya. I'm a student at the University of California, and I'm a student at the University of California.

[00:40] Harper Igarashi and I'm very excited to be here today with this excellent panel and we are here to discuss the research and evidence to advance the new agenda and this is at the intersection of course of climate change and mental health. So as we heard earlier climate change is not just about

[01:00] environment, it affects our mental health as well. And despite these growing challenges, we don't have enough research yet. There still needs to be more. And moving forward, we need also global collaboration to bring mental health into the climate action and policy agenda.

[01:20] Today I'd like to introduce our panel and I'll start from here to my left. We have Emma Lawrence, who's a leading researcher on climate change and mental health and she also leads the Climate Care Centre at Imperial College London and also the Connecting Climate Minds Initiative, which provides a global perspective.

[01:40] on research efforts in this climate change and mental health space. Then we have John Aruta, who's an environmental psychologist and associate professor at De La Salle University in the Philippines. And then we have Christina Cruz, who's a psychiatrist and global mental health researcher

[02:00] University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. And Christina's work spans school-based initiatives in India and also the Philippines and the US. And next we have Rayna Sauburn, who's a climate health researcher and also a long-time contributor to the

[02:20] our Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, and also former head of Heidelberg Institute of Global Health. And finally, we have also Ronald Mutasa, who's a public health expert and economist with the World Bank. So I look forward to seeing you again next week.

[02:40] forward to the discussion that will not only deepen our understanding of this critical issue. And so let's begin with each of our panelists who will provide their opening statement. And I'll start with you, Emma. Yeah, thank you so much. Renzo kindly asked me to use some slides just to sort of see

[03:00] at the scene of connecting climate mind. I might just go to the podium. I can see. We have to go? Okay, they're getting a moment. I might just introduce myself a little bit while they're getting everything up. So as you know, my name is Emma. I grew up on Ghana lands in what's called

[03:20] the Adelaide Hills of Australia. So I was very privileged to be surrounded by trees, by nature, by birds, by koalas. And it was always inherently obvious to me how we're deeply connected, we're a part of nature, not a part from nature. And so what we're doing to nature, we're doing to

[03:40] doing to ourselves as well. And I've got a little nephew now who I'm completely brainwashing. He now claps when he sees trees. We do a lot of we do a lot of pattying of the trees and things like that. So yeah I'm very lucky but I've also seen it change. I was just just came from Adelaide and it was 45 degrees the day before I left and the

[04:00] were putting out water for the koalas outside my family's house. They were coming down from the trees to put their paws in it to try and cool down. But it's hard when you see the landscapes changing and the trees dying, the animals dying and struggling. So yeah, anyway, that's a little bit about the

[04:20] context of where I'm coming from in the world. But I'm now based in the UK at the Climate Care Centre, an Imperial College. And for the last six years, I've been looking at these interconnected crises, come to this from a background in neuroscience as a climate activist background.

[04:40] when I was a young person myself and with my own lived experience of severe mental health challenges and it's extraordinary actually to be here and just to see how far the conversation on mental health has come from when I was first diagnosed you know over two decades ago now and being completely taboo.

[05:00] and really not knowing what it looked like to have a mental illness outside of this idea of being in a straight jacket or something in an institution, to where the conversation is now about mental wealth and the idea of resilience and of love and community and connection that's come out so strongly.

[05:20] in this conference and the importance of centering that and of centering joy and belonging in the work that we do in mental health. So yeah, I'm just very encouraged to be here with you all. I'll just put this down. I think this one works as well. So just to very quickly situate, obviously you're all here because you know that mental health is still

[05:40] a huge concern. But just to note the quote on the bottom, this was from the Lancet Psychiatry Commission on Youth Mental Health that came out last year talking about entering this dangerous phase for youth mental health. But they really highlighted how global megatrends are sort of underpinning

[06:00] maybe in driving some of this rising distress and one of those trends which is again deeply interconnected with other challenges being climate change. Again we've heard a lot of this so it won't dwell too much but you know we are at a critical time not just on climate but on crossing these planetary boundaries of how to live.

[06:20] how, of what we're taking from the Earth, certainly in the richest parts of the world, being so much more than what is sustainable. But the thing is that, and the big gap is that people really want change. And so people care a lot more than we think that they care.

[06:40] have shown this, that actually there's a big gap between what we think other people care about and what they actually care about. And there's big narratives that are being driven by trillions of dollars from like billions of dollars at least, I think trillions now from fossil fuel companies, to really put the onus on us as individuals rather than a collective sense of

[07:00] of action and connection. So how do policies align with these desires and also support people through change? You know, the world is changing and it needs to change further. So how do we and just to say that the IPCC reports and we've got one of the authors here today, they say that resilience in the latest report

[07:20] is not just the ability to maintain essential function, identity, and structure, but also the capacity for transformation. How do we build this capacity for transformation? So if you care about mental health, why does climate change matter? I mean, it's encouraging your all here. So it's a little bit of a rhetorical question.

[07:40] this point. But climate change is a risk multiplier. And so whatever we're working on, unless we consider climate change and move rapidly in the energy transition, the consequences of climate change will undermine progress on health and equity.

[08:00] And, but conversely, actually the research on the world that we need to build, what is a mentally healthy world, that strongly aligns with what is needed for a sustainable decarbonized world. So, you know, we're actually working together, you know,

[08:20] same region. So health is a powerful lever of climate action and actually as people who have power in the community and a trusted voice in the community, you have power to speak up about the need for climate action but to centre it not just as something out there and an environmental issue but actually a human health issue as we heard.

[08:40] And psychological resilience is vital for this transition and coping with the compounding stresses that people are facing. But we're here to talk about research. So while these needs are escalating and there is evidence that's really wrapping

[09:00] I mean, it's almost exponential from a very low starting point. We see that there's key gaps in actually defining the mental health burden, what is the nature, prevalence and severity of it, how do we measure the cost of inaction, and the benefits of action, the mental health benefits and risks of climate action.

[09:20] The mechanisms and pathways that they're complex. We've had so many already, but they're interacting and how do they work? And also what are appropriate mental health interventions? And there's a there's an evidence gap even though there is great work being done on the ground around the world The field at the moment is also

[09:40] also very global north heavy, as you see in this cartoon. It's disconnected between all the different disciplines that need to come together between research and policy, between lived experience and communities, researchers, policymakers and between regions. And it's unequal. There's certain topics and regions that have received more focus.

[10:00] When you talk to most people about climate and mental health, they think immediately of eco-anxiety, but they don't think of someone who's, you know, as you said, experiencing like gender-based challenges because they can't access clean water. And it's siloed within funding and policymaking.

[10:20] So Connecting Climate Minds was created to try and address these challenges. We've heard a bit about it already and I've worked with lots of wonderful people in this room and on this panel. We had seven regional communities of practice aligned with the SDG regions. They all had conveners, co-conveners, lived experience advisory

[10:40] groups and youth ambassadors who were forming the central team across the region and then they were interfacing and building that connection across the region with people from all sorts of backgrounds. Globally there was a lived experience working group who led research and action agendas by and for young people, indigenous communities.

[11:00] small farmers and fisher peoples. And myself with the Climate Care Centre and the Red Cross, the Red Crescent Climate Centre, we're helping kind of globally coordinate this. So this is just to show you how global the team was. These are just the leads, not everyone who was involved. There was over a thousand people from over 100 countries ultimately involved.

[11:20] We have seven regional agendas of research and action. We have three agendas for populations facing amplified mental health climate change impacts. And these were synthesized into one global agenda. And so the global research and action agenda is trying to target research.

[11:40] to ultimately provide the evidence that will help decision makers to act and provide an action strategy for how we do research, which we heard was as important if not more important than what research is done, and to build an understanding among diverse audiences of their roles. How do we bring people into this emerging transdisciplinary field?

[12:00] really heard from from dialogues these agendas were created through dialogue there were over 30 dialogues around the world and surveys and global events and we heard time and time again of the compounding mental health risks and multiple interacting pathways and mechanisms so it's not just now like you know disasters have always happened but it's not just now

[12:20] wants off, it's more frequent, it's compounding, it's interacting. But also that there is relevant knowledge and solutions held in diverse disciplines and cultures that we need to be learning from, working with, understanding, and particularly diverse expressions of mental health, which I've already heard a bit about as well, that we-

[12:40] There's not one size fits all when it comes to describing and talking about what we mean by climate and mental health. And so there's a need for foundational field building. And just to finish in the words of Hope Lequois, who's one of our wonderful team members from Salsivis in Nigeria, he said, it's my desire that this word

[13:00] inspires meaningful lasting change that honors the courage and meets the needs of vulnerable people. So what we've heard so much is not just about vulnerability but unique sources of resilience and working towards that vision of where we're better connected and where we can help people actually not just survive but thrive.

[13:20] We hope that you join us and you can check out this hub.connectingclimatemines.org. You can join the collaborate area, meet others from around the world, check out the toolkits that created case studies, lived experience videos and all of the agendas. And you can see some familiar faces at this gathering.

[13:40] in the Caribbean almost a year ago. So this is kind of a reunion for Connecting Climate Minds. And we want to expand and extend the invitation for you all to join us. So thank you so much. Thank you very much, Emma. So next, how about John?

[14:00] can share your opening statement.

[14:20] Hello, everyone. Good morning. So, apparently my slides are not available, so I'm just going to do this.

[14:40] I'm John. I'm from the Philippines, the most climate-vulnerable country in the world. We have more than 7,600 islands. Sea level rise, we feel it firsthand. We are based in Southeast Asia region where heat increase

[15:00] temperature rise is very much felt. In 2024 we experienced unprecedented increase in temperature. And for a poor country like the Philippines living in little ovens, it's really a real struggle. I remember my earliest memory of climate change was

[15:20] when I was a little child, probably three or four, there was a huge typhoon that hit the Philippines. Our semi-concrete house was damaged. I remember the roof was flying, the I remember the wall

[15:40] was disintegrating, and my mom, I saw her in the corner of our house, kneeling and crying and praying. In the eyes of a child, that's something that you would never forget. It was so traumatizing. And fast forward 30 years, I turned

[16:00] out to be a mental health professional working in the climate change space, providing mental health services to young people, children and young adults in my country. As an adult, the turning point really for me was when Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest typhoon in human history,

[16:20] 6,000 people died. That's an underestimation because thousands of others were missing. Thousands of families were displaced. Until now they don't have proper houses. And we volunteered to provide psychological first aid. It was tough because how could you provide psychological first aid when you have a child?

[16:40] you see dead people on the street. You yourself was traumatized as well. And so I realized that I could apply my training in psychology to help in fighting against the climate crisis. And if you attended our

[17:00] workshop yesterday, you know already that I work on climate change and mental health. But one thing that I did not mention enough is that I work in the climate justice space. Part of my work is I look at how different forms of climate injustice manifest psychologically or impact people's mental health.

[17:20] that people in the global South are more impacted by the climate crisis, but also by the mental health consequences. And women are more impacted by any disaster, including climate change. When disasters happen, they have multiple layers of consequences and responsibilities. COVID tells us a very important thing.

[17:40] important lesson on that. It's also an issue of intergenerational justice, where young people who did not cause climate change will face the increasingly severe consequences of the climate crisis. So I tried to make that part of my work. In the Philippines, we are a hot spot of murders of environmental

[18:00] So there are initiatives where I lead developing mental health interventions specific for environmental defenders in the Philippines. And I had the privilege of continuously working in that space. And I just want to share that I'm also part of the Connecting Climate Mind.

[18:20] I had the privilege to work with Rensoo Toccole, the East Asia and Southeast Asia part of connecting climate minds, where we identified what's missing in the climate and mental health nexus in the region. What do we know, what we don't know so far, what would be the next research and action agenda in the next coming years?

[18:40] what would be the pathways for us to really understand the connection between the emerging climate change and mental health space. I would like to tell you more when I share during the final discussion, but for now, thank you so much.

[19:00] Thank you very much John. Okay next Christina. I'm just gonna sit here if that's okay great. So I'm Christina Cruz I'm a child psychiatrist, global mental health researcher. Much of what I do is in schools teaching teachers how to respond to students in the moment of mental health crisis or struggle so that in that moment the child's

[19:20] gets a micro dose of therapy and then they get better and I introduce that to say that that's how I think about climate change and mental health as part of the whole thing. As a physician and a researcher we see that research is important, it is what you can feed to policymakers and should be the basis for health.

[19:40] of care and on average it takes 17 years for it to come into practice. And so what I my message today is going to be about working as quickly as we can to get the evidence we need and then to move and that's behind what we do in my program T-Leaf because whatever we think is happening that someone is suffering right now.

[20:00] now and we can do something right now. And so I think to be able to move quickly, the way one does in psychiatric emergencies, which is what I'm used to clinically when I practice, I'm an inpatient child, an adolescent, and eating disorder psychiatrist at UNC when I'm practicing, we know we need to move. And so that's where I want to start from today is let's do the research, let's do it quickly, and then let's move.

[20:20] Because the disasters like in the Philippines, as John was saying, is already happening or in schools, kids are already falling behind. And we know with climate risk multipliers, Ahmed said, it's just getting worse right now. So we don't have the time to create the most beautiful of studies. We put stuff out there and we go. So good morning, everybody.

[20:40] Thank you very much, Christina. So next, Reiner. I'm Reiner Sauerborn from Heidelberg in Germany. I'm a pediatrician, and in my path towards coming here, I became first global health.

[21:00] public health physician and then a researcher interested then in climate change since 2000. So 25 years and I'm at the University. So we are trying to research the link. There are 120 and counting climate-sensitive diseases.

[21:20] diseases that are aggravated by climate change. And mental health is a big chunk, but not the only chunk. So since this is about research and evidence, I thought I will share with you how we approach the issue from a research angle. So climate change...

[21:40] you can't study because it takes 10, 20 years to change. So usual research projects are three years. You get funding and then you leave. So you can study weather variability as a proxy and weather goes up and down and up and down and up and down.

[22:00] Most mental, and I'm not an expert, most mental disease, particularly mood disease, go up and down and up and down. So any cross-sectional shot is going to be biased. It's going to be wrong, misleading. So in an ideal world, you would follow a community for 10, 20 years.

[22:20] in its up and downs and up and downs of health and relate this to the up and downs and up and downs of let's say temperature events, extreme events, they come and go. So you need to be longitudinal. How is research usually done? The low-hanging flu

[22:40] Meaning you go to a hospital, where are the mental health patients, when were they admitted, what was the temperature before? Easy. We all can do this. And you find, lo and behold, there's a strong heat relationship of almost all mental diseases.

[23:00] And I thought it's mainly depression and mood disorder. No, it's schizophrenia. It's organic. It's dementia. It's neurotic. So that's the low-hanging fruit, because not everybody goes to the hospital when they feel bad, particularly not the mental health people. So we see that.

[23:20] We used another tool, which is there are 65 cohorts, quote, meaning whole populations, let's say communities, 100,000 people followed up some for 60 years in West Africa, some for 10 years, there are some in Seco, we are going there in Malaysia.

[23:40] some in Indonesia, Salman, Kajamada, and so forth, and in Africa. And they are, everybody is registered in a computer and you follow them by regular visits. How do you feel? Well, I come to the how do you feel, but what illnesses have you had?

[24:00] And then there are apps. How do you feel today? Not today, now. EMA, ecological momentary assessment. Yeah. With my wonderful team sitting there, from whom I'm learning to do this. So you have the minute you

[24:20] You get this question, how do you feel today? Like you asked, how do you feel now? And then you do this every day and then you get a profile of mood, which is a good indicator for a lot of problems. Yes, you can do the WHO questionnaire. It's a 50 question. There are small.

[24:40] and we are integrating this now into these cohorts, which have followed up for a long time. We call it CHEERS. That means climate and health evaluation, early warning and response. I sent you the paper. If you can share it, if somebody is interested.

[25:00] read it and I think that should be one of the Philippines and there's none. You're an established one. Yes. So that is a kind of glimpse. It's very difficult to do research on the link between climate change and health, even more to evaluate interventions that are so important.

[25:20] supposed to alleviate at least a climate impact on mental health. There are ways, you know, some drug reductions or increasing how mental health patients living with mental health problems are registered by their patients and they get some

[25:40] how to behave and very often they're not aware of the threats and so forth. So there are adaptations as we call it in the climate world or meaning protection measures for them. Thank you so much. Time is up I read. Thank you.

[26:00] Thank you so much, Rayna. Next we have Ronald. Thank you. So hello everyone. I'm Ronald Gantassa. I'm the manager for the health practice at the World Bank.

[26:20] East Asia and the Pacific region. Just want to acknowledge our counterparts in the national interest of Singapore, Dr. N.Clare, for their partnership and also quite a few of the government counterparts across the region that we work with, Indonesia, Mongolia, Vietnam, who are here in the room, very delighted to.

[26:40] CEO. So of course I come from a development bank and we work with governments to really to prioritize important policy actions that not only have good public health implications, but also the economic implications. So quite delighted actually.

[27:00] that we have this opportunity to meet practitioners, researchers, and also policymakers and influencers. I will just begin by mentioning two points. The first part really that's very crucial is to understand how climate

[27:20] change in mental health, basically indirect. And the first part is basically the direct pathway. Based on the work we've been doing in the World Bank, we know that there is a lot of direct impact, particularly in terms of distracted access to healthcare, trauma, and also displacement that impacts the significant chunk of the population.

[27:40] particularly for the archipelagic countries, Philippines, Indonesia, as well as, of course, a lot of our Pacific counterparts. So developing a clear understanding of that direct pathway, obviously, is very important. And of course, this is where I think the researchers come into play because why is it important is because how the

[28:00] that impact happens differs by country and also by context because of geography and also because of way of life and also because of the physical infrastructure within which this country is developed. So it's a very important area that we need to develop knowledge around and of course that basically leads you to very practical and concrete action. Second area is the

[28:20] pathway, basically looking at the political, social and economic determinants of mental health. And by looking at the social and economic determinants, it's also very critical because we do know that the climate change related impacts on mental health tend actually to affect the poorest segments of our society.

[28:40] And that's why the segment is actually the one that is least prepared to cope with the impacts. It's also the least prepared to recover after a climate related shock or event. So it's going to be quite important that we also apply an equity length in our development of research and knowledge and also the policy actions.

[29:00] that we should be taking forward. So in the World Bank we do support what we call policy research, which is research not for the sake of just research, but it's research that really meant to influence policymaking. In our conversation with the government of Indonesia in December, they were very clear that look, there's an act, slow, slow,

[29:20] growing acknowledgement that mental health is such an important issue for one of the largest economies in Southeast Asia, but it's not yet there at the top of the policy priorities. So in our conversations, we sort of like we're discussing how do you do the agenda setting in order to move mental health to be on top of the policy priorities. So it's great that we have this opportunity.

[29:40] which I do feel is actually an Asia-wide agenda setting. So many thanks to National Inverterial of Singapore for pulling this off. I'll stop here for now, otherwise I'll get flagged for being over time. Thank you. Thank you very much, Ramald. So as you can see, we have our panelists here.

[30:00] from across various disciplines and geographies. And we heard about some of the gaps that still remain, how can we translate that into policy? We're going to have a few questions. I have a few questions for you all, and we'll also have time for questions from the audience as well. So I'd like to start with.

[30:20] Emma. So you talked about the gaps that remain. Could you go a bit into more about some of the emerging themes that are, that you found during the research? Yeah, thanks so much. So the research, the global research agenda has 53

[30:40] priority research themes. We were trying to consolidate but there's just there's so much richness you know this is a really big area when you when you start to unpack it and also globally. But that was under four key priority areas and as well as the foundational themes. So I spoke about

[31:00] about this kind of conceptualization. We talk about climate mental health, climate mental health, but what do we actually mean by that? How does that get measured and described appropriately, particularly when we're looking at different cultures, different communities around the world? And how do we,

[31:20] bridge that need to be very locally focused with the big-picture perspective of actually capturing the mental health burden associated with a changing climate in order to push policymakers and funders to invest. And also how do we measure, when we're talking about measuring, evaluating

[31:40] interventions was actually important to measure here what does success look like, what are we capturing. And so that foundational field building, also capturing what already works, what methods are coming in from different disciplines into this very transdisciplinary field. And there is some work that we're doing based on that.

[32:00] working with Professor Gary Belkin and his COPSquared network. We're bringing together the Connecting Climate Minds network with his network is already working with people on the ground who are implementing climate adaptation and resilience and integrating psychological resilience, mental health support into that, but we're then starting to partner and say

[32:20] how do we sort of accompany, as researchers accompany this work, and share, learn from what's working and share the kind of key lessons up with sort of multilateral fora and back down to the ground. So we're trying to put those things in place, but that's the sort of foundational themes.

[32:40] The four kind of high level categories, the first was impacts, risks and vulnerable groups. So again, you know, how do we capture and understand these risks? There was an impact and there were sort of definitely a lot of subthemes, but we heard yesterday also around the

[33:00] interaction between, you know, what we sort of talk about as climate change with ongoing historical and current traumas of colonization, of other sort of extractivism, of commercial determinants, of political determinants, of environmental determinants, of social determinants, biological

[33:20] So there's a lot of different impacts and then this goes into the, and groups that are affected. And then this goes into the second category, which is pathways and mechanisms. So how do we actually understand the multifaceted ways in which a change in climate ultimately interacts with mental health?

[33:40] also the other way, right, that how does psychological resilience interact with our capacity to act, how does climate action interact with with mental health and what are those pathways, and that goes into the third category which is how do we actually capture and measure the benefits.

[34:00] sometimes the risks of full mental health of climate action because also we should acknowledge that sometimes conservation efforts can displace people from you know their communities there's there is and you know people are losing their jobs in the energy transition so there is that's that's you know a small fraction compared to the

[34:20] massive benefits that can come, but it's still important to acknowledge that there are risks as well as benefits. But there are benefits on multiple levels of individually, communally, at a society-wide level, if we think about changing buildings or more trees in cities.

[34:40] trees and how that provides the climate adaptation cooling effect, particularly for vulnerable groups who are more vulnerable to the urban heat island and the mental health effects of heat. So it's a climate action but also mental health action, but that's not really being captured yet. So how do we measure and capture that? And then finally, what are the mental health interventions that are appropriate in the context?

[35:00] of a changing climate. And sometimes that's interventions that already exist. And when we say interventions as well, that's quite broad, right? There's a range of tools, support, solutions. But then also there might be some new things that come. And John talks about, you know, climate-aware, mental health professionals. What are the tools that can already be applied?

[35:20] and what's different, what's unique about the context of climate change, even for disaster psychiatry when there's, you know, people aren't able to have the time to recover before the next disaster hits, you know, what are the implications of this. So those are the four kind of high level categories. Okay, great, thank you so much, Emma.

[35:40] You talked a lot about the most impacted, of course we know vulnerable groups and you talked about some interventions and that brings me to actually I have a question for both John and for Christina you can answer separately, but I know that you are working in, most directly with vulnerable groups and working on interventions. So starting with your question.

[36:00] Starting from John, I'd like to hear more about some of the interventions that you're doing on the ground in the Philippines. Thank you, Niaia. So far, the interventions that we use are not really specific to climate change and mental health because it's an emerging field. So we need to draw from the existing interventions in the mental health.

[36:20] field. In my practice in the Philippines, we, I personally experience an increase of intakes reporting climate related problems or distress. So for example, there's this medical

[36:40] medical personnel who has been my patient in the past one and a half years and then one time he goes to Vietnam during the summer, you know, the 2023 at the time the unprecedented heat. She is diagnosed with generalized anxiety.

[37:00] disorder and she was healing after several, you know, recovering managing after several weeks of therapy. And then she went to Vietnam, feeling well and then went outside to go to the market and then suddenly she felt all the symptoms. You know, there's no particular trigger except heat.

[37:20] And then she was rushed to the emergency room. And then she reported that there are five other patients in the emergency room reporting the same symptoms, reporting that it was the heat that triggered their distress. But this is just an example that climate change can come

[37:40] in different entry points. It can either trigger or exacerbate already existing mental health problems. So we use the existing interventions that we have, and we hope that the direction in the future is that we create climate-specific interventions. But one hopeful impression

[38:00] hopeful about the nature-based intervention because we know in evidence that exposure to nature provides not only reduction in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, but also increase of well-being and flourishing. Mental health is not only absence of psychopathology,

[38:20] presence of a flourishing life and well-being. And nature-based intervention, I think, is very important, especially in developing countries, like the Philippines, many countries in Southeast Asia and South Asia, because this is a low-cost intervention, especially when we don't.

[38:40] Our governments don't allocate sufficient funding for health in general, more especially the always neglected mental health. Now, nature-based intervention can come in as one of those potential interventions for mental health. Thank you. Great. Thank you so much. So, Christine, I know you have

[39:00] the Tea Leaf project and so I would love to hear more about that and I'm sure everyone else would as well. I'm happy to talk about it actually doesn't quite address climate change and mental health. So I'll talk about it a little bit actually talk about what we are doing climate change and mental health. So Tea Leaf is about teachers being empowered to address students' mental health in the moment for great

[39:20] rates K to six. The way this is applicable in climate change is because kids are coming in with all kinds of stressors, right? That family is under economic stress. We know actually biologically that as temperatures go up, we see increases in psychiatric hospitalizations. I think the

[39:40] way to boil it down is essentially we're human and we're made of protein and as the temperature goes up our protein starts into nature. That's kind of the simplest way to think about it, but true, right? Behind the scenes what's happening is there's a dysregulation of something called the HPA axis, so adrenaline is coming up more, so you're actually more stressed. There are changes to what's going on neuro-

[40:00] biologically, changes in serotonin levels, changes in dopamine, this all leads to things like increases in psychotic breaks, increases in panic attacks, that kind of thing. Truly, our resistance goes down because of heat. That is biological, that's, you know, kind of unequivocal.

[40:20] That being said, as a child psychiatrist, my undergraduate degree was in business and then I also have a master's in education. And so to me it's way beyond the biology because what we're talking about with climate is an entirely changing ecosystem. So what we're doing in Darjeeling, India with my partner Darjeeling Laid-in-Lemorow Prana,

[40:40] Priscilla, Curie will be in the next panel, and supported by the Marimala Health Initiative with Preeti being here today. We're looking at how to empower farmers locally to become more resilient. And we say that in that for better, for worse, and this is my own personal opinion.

[41:00] is that climate change is happening. I'm not sure what's going to change right now. I hope it does. In the meantime, people are suffering. So we're taking, bringing people back to their roots. And this is also done with Mike Maturge out of Broadleaf and then Megan Cherub out of Colorado thinking about cultivating growth where,

[41:20] we're figuring out what exactly our farmers are needing, where farmers in India have amongst the highest suicide rates in the world right now, and understanding how they can become more resilient. And it frankly boils down to economics and how to diversify their income stream, how to diversify their farming practices. And so that's the route we're actually taking. It's very much-

[41:40] a sociological approach, not at all medical because I can only do so much when someone comes in with heat problems, right? The heat is still going to be there, but I can change how they operate. So again, Priscilla is going to talk about this a lot more and is leading the charge. I'm looking at her now. But I think that's the approach.

[42:00] that we need to take is it has to be kind of like a whole field multidisciplinary approach, because for me, psychiatry medicine, it's a band-aid. We need to get to the root of it. And as we don't quite know how climate will change and what it's going to do, we've got to act now with people suffering now. So that's what we're doing.

[42:20] Okay, great. Thank you so much. So I'd like to move on to Rayna. So given your work with IPCC, how can climate mental health, the research be better integrated into the discussions on policy?

[42:40] That's also something that Ronald mentioned. I also am very much against research just for research's sake or for career progression and so forth. I think every research should have an impulse to those

[43:00] been researched to the communities and also picking it up the policy letter. The IPCC, the one report that I was a part of, did not specifically mention mental health, I am ashamed to say now. And unfortunately, I'm no longer one of the lead authors, but maybe

[43:20] I can sneak it in through the back door and I hope I can because for me this is also a mental journey here. I'm not a mental health specialist and I learned so much and I thank the conveners again for inviting me to this conference. So I think the cops are now.

[43:40] the climate conferences are now the targets for us. And with my team over there, Julia and Sandra and whereas Jamila, they are... We want to go to Bel-Emm as we have been going to all climate conferences. But I am ashamed to say I never said the word mental health.

[44:00] But now I will and we have empirical data. Yeah. Now we have empirical data from Brazil, because Julia is from Brazil. Julia, can you stand up, please? Julia is a medical student and a wonderful medical student and she has done this low-hanging fruit research in Brazil, but also now establishing a cohort.

[44:20] these data we want to share and talking truth to power. That's the only thing we can do as scientists, but we cannot just publish and turn the page. So I am completely with you and maybe we should have a talk too.

[44:40] truth to power, how can the World Bank put this up on their agenda and so forth. So yes, and also I think we should start with where we are. We should not always go to foreign lands and so forth. What can I do myself? Eat electric.

[45:00] cars and on my own footprint is 11 tons per year. This is much too much and I've brought it down to six. Well we need to go to two, which is tough. Everybody has to do this. Then we have to work at the workplace. We have done a study on the carbon footprint of our University Hospital and people fell off

[45:20] I can invite you to do this here, Singapore, and so forth. And then the city, we work. And then the country. So this policy starts from us and then goes to the COP. So I think we should have some discussion.

[45:40] have a multilevel, to put it in a very fashionable term, a multilevel policy implication approach. Thank you so much. And, Emma, you wanted to add onto that a bit? Yeah, thanks. I just wanted to in case people aren't familiar. So the last intergovernmental panel of climate

[46:00] changed reports came out a couple of years ago now. They mentioned mental health for the very first time. So they had a section on mental health and the evidence on the impacts for the first time. But actually throughout, even there's one mental health section on impacts, throughout the reports it talks about the need for like community participation, it talks about well-being.

[46:20] It talks about countries with higher participatory governance, higher trust, lower inequality, have lower emissions and higher wellbeing. So these things are deeply interconnected and sort of inherent throughout the work. But one of the people, one of the IPCC authors, Dr. Freddie Otto, who's part of

[46:40] connecting climate minds, she was really pushing for mental health to be in the IPCC reports. You said one of the challenges is the lack of data, particularly from around the world. So they're wanting to put it in, but sometimes there's just the gaps in the data. And similarly, so COP now have been...

[47:00] We run the first ever climate and mental health event at a cop-in, so it's never been mentioned at a cop until, or a climate cop until Glasgow cop 26. And then a couple of years ago, there was the first of a health day at a cop and it was a climate and health declaration and one of my colleagues was working with the.

[47:20] presidency, she was the health envoy for COPP and she managed to get mental health and wellbeing in there. But it wasn't in the draft. She had to work to put it in there. So we've got these mentions in there, but it's how that then translates into the actual funding for climate and health. A drop of it goes to mental health. So even though it's in there, it's still the advocacy needed to

[47:40] to make that change into the resourcing that can make the change in the research. And I completely agree with everything that's been said on needing to move quickly and not to do research in traditional ways that does the research and then you go, you know, that be aware of working directly with the policymakers of the people on the ground. But when the World Banks asked me and my team, you know,

[48:00] what should we recommend? What is the best by intervention? And the truth is I can't tell them that because we don't have the data, right? So be interested, again, if you know, we're trying to learn what is needed for the people who are then trying to invest and make the decisions. And sometimes it's, you know, the impacts are there. It's just how are we capturing that?

[48:20] that, how we can then say to the World Bank, well actually this is the evidence, this is the best buy, this is where you should tell countries to put their money. Thank you, thank you. And that also leads to my next question actually for Ronald. So what, you know, can you give us an idea of what funding mechanisms can help scale the mental health support process?

[48:40] particularly in low and middle income countries. Thank you. Obviously I would not want to claim that the World Bank is coming to the table with a ton of money for research. I think just to put a disclaimer upfront, but there are two important things I think in climate.

[49:00] climate change and mental health research. Number one, I think, is the work that looks at the mitigation parts in terms of, as we were just mentioning, what can be done now to minimise the carbon footprint because, of course, the problem

[49:20] keeps growing, the risk keeps multiplying. And then the second bucket of work really centers around the adaptation in terms of how do we sort of like manage and live within a reality of the fact that of course climate change impacts are really manifesting themselves in greater mental health challenges across the world. So those are the two buckets.

[49:40] of work streams that we do support. The work actually goes way beyond my practice. It also involves infrastructure and several other parts of the economies. But to come to your question, there are a few, I think, important points. Number one is the World Bank engages a lot with minuties of five

[50:00] finance, and those are the most important entry points in any economy in terms of financing and prioritizing funding. External financing comes in, but in my view, especially in Asia, a very dynamic region, lots of economic growth, lots of capacity. The first point that we need to break is basically getting the measures of finance.

[50:20] to allocate more resources towards mental health and climate adaptation. That's the first point and most important because why? Because that's actually where the bigger, long-term and more sustainable financing would come from. Because we can come in or invest can come in, but it's probably very narrow and focused on a particular issue. Very delighted to hear that.

[50:40] Singapore as always. I think you have been trailblazers in breaking through that cycle and getting the financing to prioritize. Second point is what surveillance mechanisms do we put in place, especially in the aftermath of disasters? Because I do feel that's where the data that you're talking about is going to be.

[51:00] really could come in quantifiable ways that can actually then be used in a long time. We do reports in the World Bank known as climate change development reports. We used to call them diagnostic reports, but we moved away from that. And my colleague Dr. Sen has been involved in that in Vietnam, where we really have been looking at what data exists,

[51:20] to highlight. For example, in Philippines we know that the eastern seaboard provinces that tend to get impacted most by typhoons, the families get disrupted access to health care, but there was no rigorous evidence that we could use when we're doing that report. Same thing when you look at like eastern Indonesia and the Pacific. So the first part is

[51:40] What surveillance mechanisms do we have that really can help generate data on an ongoing basis? Because it is out of this surveillance system that you actually can be able to generate hopefully more meaningful and long-term data. The next part that I wanted just to mention is around some of the community-based individuals.

[52:00] have that response to the climate change health and mental health nexus. And here I was with Dr. Liu in Korea with Dr. Ann Kley in June where we were engaging with some of the stakeholders in government and outside government.

[52:20] government in CO that are basically implementing community-based interventions. Because why community-based interventions? I do feel that mental health, climate change nexus requires very practical, targeted, and tangible actions. It's not something that you can keep in a way of ventilated

[52:40] rooms, you really need it to be on the ground for it to be real. So I do feel that a combination of government financing, maybe development bank financing, but most importantly, also foundation financing that really goes towards supporting well-designed interventions at the community level is going to be very critical. When we're in Korea, we actually sort of like of course

[53:00] confronted by a reality in the dimension of mental health. Partly, of course, lead to climate change that we're not so used to, which basically was the teenage mental health crisis because kids are mostly like indoors, on gadgets, and isolated. But how do you then come with intervention that basically would target, get to

[53:20] get to that cohort in a very effective way and a practical way, which is obviously where the community-based and well-targeted cultural-sensitive interventions would come in. So I just would really like to sort of like challenge all of us in this room that we, I think we have to look at the response to the climate change mandate.

[53:40] health nexus, I think is a core for us to have a community of practice that actually brings together development banks, academic institutions. For me, most importantly, the treasure is of the country because, of course, at the end of the day, what gets financed in some ways gets implemented. What doesn't get financed?

[54:00] even if it's well designed on paper or intention, never happens. So let me stop with that, but I do really feel that this is a very good convergence and I really hope that we can begin to build a community of practice, including of course activists going forward. Thank you.

[54:20] also take some questions from the audience. So if you have a question, please make your way to the middle. There are microphones there and if you could give us your name and where you're from. Okay, we'll have about two to three questions. So okay, we've got four people standing. So let

[54:40] just do you four that are standing right now. We can take your questions and then we'll close up. So first up on this side on my left. Thank you. My name is Bryden, I'm a psychologist from Australia and my pronouns are agin. I'm also a neurodivergent as well.

[55:00] love the discussions here so far and we've got the intersection of mental health and climate change. We've also talked about the importance of data and collection to be able to inform decision making and funding. I'm curious how minorities such as

[55:20] as the LGBT community and intersections within that, and the neurodivergent community, because neurodivergence is a neurodevelopmental issue, not a mental complication. How might we be able to capture the data or the experiences of those minorities and those intersectional

[55:40] minorities within the data of research and health intelligence so that they're not forgotten or not heard in mental health and climate change. Okay so I collect okay

[56:00] So that's the first question. We'll collect all the questions and then we'll have the panelists answer. Okay, we'll just start with this side. Everyone can go and then we'll get your question to us. Yeah, thank you very much. My name is Afi, I'm from Indonesia, where the hardest country may be on the earth.

[56:20] So I'm interested in what Professor Rayner is taking with the correlation with the heat and also with the mental health wellbeing because I live in a hot country where Dr. Cix can be inside their house.

[56:40] And I used to work in the same outdoor office where I have to open my laptop and feel the heat. And I feel like the stress is piled up because of the increasing heat over time.

[57:00] So I think it is correlated to how we, maybe our body is adapting with the feet over time, but actually maybe our mental health is not really well because it's, the stress is piled up over time so it's not a

[57:20] the intervention, I feel like it's not about the nature or maybe like hugging trees or something because nature is not naturing anymore, right? So maybe the intervention is like ice bath or something. Yeah, it's temperature therapy. What is, I think,

[57:40] What are other options for interventions? The intervention is not the mental health itself, but also the source of the problems. Thank you. Thank you. Next question. Hi, guys. I'm Sanjay from Bangalore, Thailand. My heart is racing right now because this is such an important thing.

[58:00] topic that we really need to discuss and I love what you share that burnout people burn the planet and burn planet burn people out as well and I think as Sean and Ronald also shared you know ASEAN is very vulnerable to climate change and 1.0 people are the least prepared to cope and least prepared to recover

[58:20] as well. And Reina, yesterday we had a quick conversation where you also shared that use losing hope and I think that loss in hope is also because the world leader is talking about drilling back into fossil fuels and that AI technology and EVs are coming up, but yet countries rich in cobalt and lithium are the ones to be exploited for these resources.

[58:40] as well. And as Christina shared, that psychiatry and psychological intervention is just a band-aid for all the issues that are happening. And then, Emma, you talked about that we cannot work in silo, but rather work together collectively to solve this issue. So how can a country that is trying to catch up economically?

[59:00] and many times are the one that is to be exploited by the global north in terms of labor and resources take charge and lead change since many countries are still catching up with the industrial revolution as well and if the panel can share any success stories from the global staff that is actually taking charge in creating change as well. Okay thank you.

[59:20] Thank you. And last question. Right here. Morning. I'm like what Georgia's Christina mentioned a colleague focused on advancing health and mental health in the eastern and Malayis, probably. My question is for Emma, you mentioned that you're not yet a point that we can recommend best buys for most impactful community based interventions.

[59:40] In your opinion, how are we going to get there? What are going to be the key drivers so that we can put evidence into action over the coming years? Okay, thank you very much. So first question was about neurodivergent and minorities and is that okay? Is it Brian?

[01:00:00] You see, I didn't take your card by chance this morning because LGBT people are not visible in surveys, particularly not as far as I know in mental health and certainly not in mental health and climate change surveys. So we will hopefully communicate on that.

[01:00:20] This is how to ask for this very taboo topic in surveys. So thank you for mentioning this. The lady from Indonesia. Yes, where are you? Ah, there. OK. Yes, you suffer from heat, and heat has a physiology.

[01:00:40] psychological effect on you, meaning stress and meaning heart and adrenaline. As Christina said, there's a cascade of neurotransmitters that's kicked off. But it also, two degrees more, halves your work capacity. That's something for the World Bank to worry about.

[01:01:00] And for all of us to worry about, and it includes mental, I mean, intellectual work. Sitting at a computer, you all know this, in the open and you stare at the screen and nothing comes. So for farmers, it's essential to work in the heat and they can't. So they are between...

[01:01:20] Either I feed my family and ruin my health and get my core temperature gets high, which is lethal, it's very dangerous. Or I take care of my health and my family goes hungry. So there is something on harvest output, there's something on intellectual capacity.

[01:01:40] Many here I've seen in Singapore, they are exposed. There is one intervention on homes we've tested that's the cool roofs. We may talk about this. So uncorrugated iron roofs or on mud roofs or even in New York to save on Asia.

[01:02:00] There is, there are particular, it's not only paint, it's a kind of plastic that insulates and that reflects the heat. And it's two degrees cooler inside as it would be without it. So maybe we could talk about this.

[01:02:20] So that's my quick comments on the heat business and on the neurodivergent. We'll stay in contact. I wanted to add for Brian's point. So part of what we do in Darjeeling and in Manila, actually, the model is called Community-Initiated Care.

[01:02:40] It's been around for a while, but only come into the literature in the last like two or three years there's a paper by Siddiqui. And so and it's backed by the well-being trust. So I think it has to come from the community. The researchers are not going to get there in time. So it's communication care starts where the community is interventions, whatever's happening.

[01:03:00] happening for me it's mental health, then becomes part of research and you somehow get it into the ethos and the literature and I think that's how you're going to have to go for your community and that we I think researchers just can't get everywhere and I'll just briefly comment on whatever is happening in the United States where I'm faculty right now.

[01:03:20] I think we really all have to take into our own hands as currently living in Manila, control of the funding of the research. And so you start with community initiated care, which is whatever the community is already doing, whether teacher, firefighter, cop, they add into their daily workflow a little bit of whenever you're looking.

[01:03:40] to do health, mental health. And so that's also how you collect your own data to then put it forward. That's part of how we've situated tea leaf in India, as well as the climate change and mental health piece. And so you need champions within the communities to do it. Otherwise, I unfortunately don't see like a coordinated effort to be able to do it.

[01:04:00] Yeah, I want to comment to our sister from Indonesia, beautiful country. On heat and mental health, there are emerging evidence that heat is related to mental health. There's very good evidence coming out from Indonesia. They have multiple.

[01:04:20] CT evidence that increased heat over time relates to psychiatric intake, that also those who already have mental health problems are less able to manage or respond effectively in times of a heatwave. There is also evidence that

[01:04:40] Heat is associated with domestic violence and sexual violence and those are good flavours for mental health problems. In terms of, we also know that our outdoor workers, as Rayner mentioned, are very much exposed to heat and therefore they are more prone to the

[01:05:00] psychological impact of that. I have some students in Manila studying commuters and this impact on their psychological health because if you commute in Manila it's like a five kilometer ride would take you two hours. It's crazy and in terms of interventions there we know that

[01:05:20] There are people who find their own ways to adapt. There are creative ways. But we know that planting trees is an intervention in cooling effect. But what I learned from conservation scientists is that if we plant trees, make sure it's a native tree. Because if it's not a native tree, the ecosystem dies. Because the other space.

[01:05:40] species don't benefit from it. So plant tree, but a negative tree. This is such a rich discussion. And yeah, please come and talk to us like in the break because there's so much more to say. Aldrin, be quick through. So Bryden, thanks for the question. I'm also neurodivergent.

[01:06:00] neurodivergence within the climate movement is something that has been I guess growing in awareness because there is a lot of unique kind of insights or perspectives that people with neurodivergence are sort of bringing to the community but it hasn't been fully captured in climate mental health yet. I have some colleagues who are working on that.

[01:06:20] that, I can connect you. But one of the challenges of also capturing that in data is often just not captured in data sets and so we're doing a project at the moment doing group discussions with young people and one of the reasons for doing that sort of qualitative work was to try and really unpack how their experiences do intersect with their identity with their

[01:06:40] culture, with their place, with all of these other things that are going on in their lives so that you can maybe unpack more in a discussion rather than in most of the data on young people that has been survey-based. Just on the question about, yeah, so slum up Hageet and Indonesian friends, but yeah, Heed and Medhavnajan

[01:07:00] Health is just one example of the many, many, many different pathways and mechanisms as well. We heard in Connecting Climate Minds, people are being trapped in their houses because it's too hot to go out. So they're socially isolated, which is increasing their mental health effects. Children can't go to school. They're saying, I can't go outside and play, so that, you know, they can't sleep. So there's, we just have to,

[01:07:20] We heard some, but there's multiple mechanisms. People with schizophrenia represented 8% of people who died in the Canadian heap dome, way higher than the people who live with schizophrenia in the population. So this is just one example, but it's really underappreciated in mental healthcare, but it's also underappreciated in how it's captured in.

[01:07:40] discussions about climate action, right, which is still often seen as something out there as opposed to affecting people, people's lives, workers, and so that's part of the narratives that we take out and try and change the conversation. In terms of the third one was on, yeah, global South, and examples and

[01:08:00] initiatives. So one thing just because of time is to say to check out the hub where we do have case studies from around the world including in the global south. But there's really, so for in Australia for instance some First Nations communities are leading like caring for country initiatives which have also been evaluated for the

[01:08:20] mental health and wellbeing benefits that come from those initiatives that are helping to sustain and actually through traditional fire burning, etc., stopping the huge wildfires that are lowering the risk that then also lowers emissions. So these links and these benefits are really important.

[01:08:40] benefits, but there's a lot of different case studies. In terms of countries, at a country level, just to know that the national adaptation plans and nationally determined contributions for countries are coming out now, which are the plans for how countries are going to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and how they're going to adapt. And it's really

[01:09:00] important to have advocacy for mental health to be considered and included in that. So if you're interested in that, also we're working and also with United for Global Mental Health on trying to advocate for that because most plans do not have that or only mention it very briefly. In terms of the interventions and how do we get there?

[01:09:20] do we need to do? I think there's a few things that we're trying to do. I mean one big challenge is honestly in the funding space. So if anyone here is working with funders, advocating for funders, like this is something that we need to just make the pie bigger in this space. But second what we need to do is also elevate and identify

[01:09:40] identify what's already happening and connect that, which is what we're trying to do through the Connecting Climate Minds Global Hub and other initiatives. The third is how do we partner with and accompany as researchers those interventions so that there is that sort of evidence around that, but in an appropriate way.

[01:10:00] And we're doing that through the development of these observatories. So if you're interested, if anyone's interested in joining that, we'd love for you to join us. And the fourth is actually how do we measure this, right? So I know some friends from Origin here are also trying to work on this. And they've got amazing work that's just getting off the ground in this space.

[01:10:20] So go and talk to them and I'm hoping to work with them as well on this project of how we actually measure. Yeah, I'll stop there. But yeah, I'd love to talk to you all afterwards too. Thank you so much. And unfortunately we don't have much time. I see some people are standing up, but we have to close up the session, but we'll be here all day. So I do encourage you all to continue.

[01:10:40] Sorry, do you have a quick question? No, just very quickly, since we're out of time, I wanted actually just to say, Emma, your work on the best buy interventions is actually very critical. I think it's an area that we need to develop more and more. And here's why. When you look at how the

[01:11:00] of health, engage with the administration of finance, always the question goes back to number one, what are the best buy interventions? Because we cannot just give you new money without being very clear on where it's going towards. So I just wanted to reiterate the importance of that work. I think with something that we need to check forward very seriously. And very quickly, I think that

[01:11:20] need to stimulate demand for action, both in terms of financing and programs, and how do we do that? Engaging also with parliament and parliamentarians is also a very good avenue, especially if you get very good leadership. Then it becomes domestic and actually more authentic than I think sort of like pushing it purely sort of like as a risk.

[01:11:40] And then my last point is, because I support a number of countries across the region, I do see that as a growing board of research on climate change and health-related risks, but it's still broad. The mental health element.

[01:12:00] is actually missing to some extent. So I think it's very important that I think we begin to engage also so that that dimension actually comes out in a very prominent way. Otherwise, the return of very general evidence that basically would not really be helpful on the climate change and mental health. Just wanted to point to this point, thank you. And actually a lot of climate and health work is already happening.

[01:12:20] You just need to integrate mental health into it. Sorry, just to say, you know, there's a lot that we can do with our colleagues in climate and health to already not reinvent the wheel. OK, thank you so much. This was a very great discussion and I really appreciate all your insights. Everyone, please thank our panelists for.

[01:12:40] And thank you, Nia, for that excellent moderation. If you have a few minutes less for coffee break, blame it on Emma. No, just kidding. No, but it's, you know, this is just a start, right? This is just the beginning and we're already having this excitement.

[01:13:00] energetic conversation. So more to come in the next few hours. So we'll just have a quick coffee break, maybe around 20 minutes. We will be setting up a climate emotions wheel wall, or not really wall, it's a board. And we would love you to indicate what are you feeling now?

[01:13:20] when it comes to climate, which Antje already started during her keynote, but there will be a wheel please visit it, and yeah, let's connect, explore, co-incubate ideas, and then ask for the World Bank for more money for projects. See you there.

[01:13:40] You